Covington Central Riverfront is a HAWT topic that everyone is buzzing about lately. Most of us know that the site was the home to the IRS processing facility for a long time, and unless you live under a rock – you’ve seen the demolition happen over the last year. But what you (and we) did NOT know was that:

The Covington Central Riverfront site historically did NOT have a distinctive neighborhood identity -instead functioning as an extension of the adjacent Mainstrasse Village neighborhood (then known as the “West Side” after its location west of the railroad tracks). The Old Town-Mutter Gottes neighborhood, which was then more fully integrated with Downtown Covington and did not have a strong independent identity, instead just being a “residential” section of Downtown. The area’s only label, which appears on some of the older maps, was the Johnston and Russell Subdivision. Over time, redevelopment, revitalization, and urban renewal eventually created distinct neighborhood identities in Covington where none previously existed. Mainstrasse Village was an identity generated in the 1970s to market the area and draw interest to the neighborhood business district, which has, at this point, become completely solidified as a distinct neighborhood identity. Similarly, Old Town-Mutter Gottes was generated to try and revitalize the area beginning in the 1980s, drawing its name from being an old neighborhood at the periphery of downtown around the historic Mother of God Catholic Church with several houses being rehabilitated by private entities, who used the identity to market the area to home-buyers. The neighborhood on the site of the Covington Central Riverfront was demolished in the 1960s, before these two adjacent neighborhoods got their distinct identities, before it could go through this process.

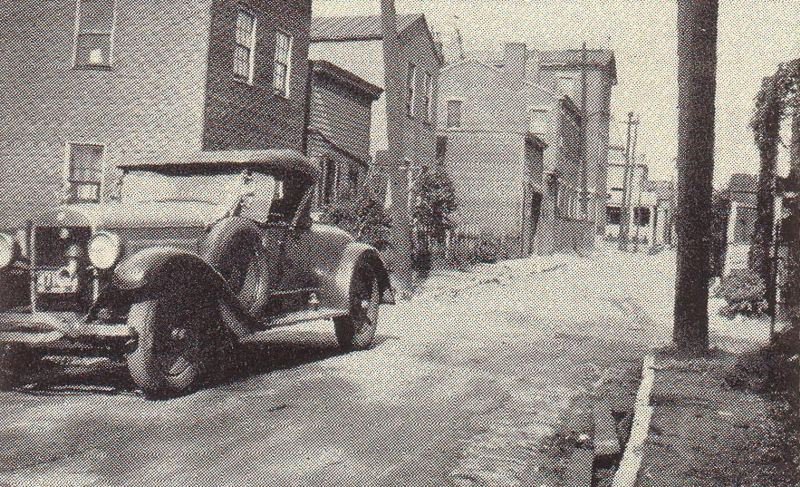

An actual photo of the 1937 flood.

The Covington Central Riverfront is in the middle of a larger area between Western Avenue and Sanford Alley along the Ohio River that was cleared of all historic buildings in the decades after World War II, and from 3rd to 5th Streets. This section of the city was historically very flood-prone and suffered heavy damage during the 1937 Ohio River Flood. The repeated flooding of the area had led to it becoming a predominantly working-class Irish neighborhood with industrial operations along the riverfront and scattered between the houses. The most famous resident of the site of the Covington Central Riverfront was James Lamont “Haven” Gillespie, who grew up living with his family in the basement of a house on Third Street between Madison Avenue and Russell Street. Upon finding success as a songwriter, Gillespie moved to the house at 509 Montgomery Street, located on higher ground, which is still standing! This was a common pattern for residents of the area, many with means sought to leave the flood-prone area. At the time of its demolition, the neighborhood was still home to a predominantly Irish Catholic population.

This map shows the affected area of the 1937 flood.

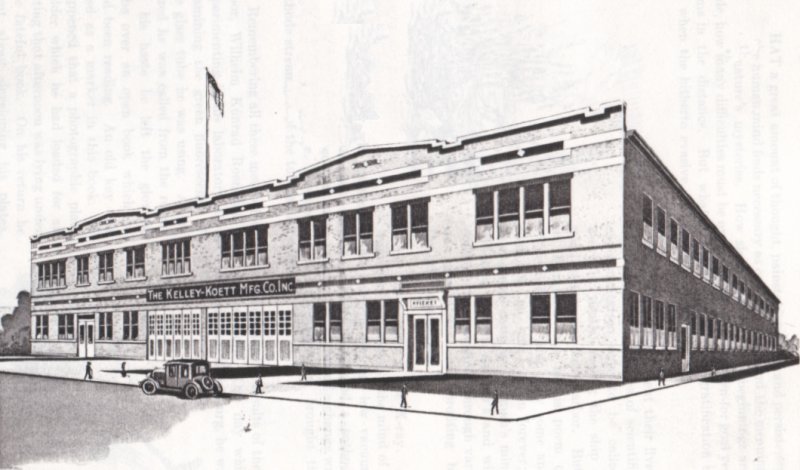

What’s so interesting to us about the history of the site is the variety of uses that USED to be there. Before the Flood, in the Covington Central Riverfront area - there used to be four giant industrial buildings - Ohio Scroll and Lumber Company, the Kelley-Koett Manufacturing Company (an X-Ray manufacturer), an unnamed electroplating company, and the Avery Drilling Machine Company. It also included an auto repair station, a grocery store, a wrecking yard, a tobacco warehouse, and a church; as well as 181 houses, 37 apartment buildings, 16 buildings of retail space, plus many small garages and carriage houses. That’s a lot of variety of uses in one area! However, after the flood a lot of people moved out of the area for fear of more flooding and damage to their homes and properties.

After the 1937 flood, people with means often would leave the neighborhoods closer to the Ohio River and Mill Creek that had flooded, causing a downward spiral of declining property values, depopulation, and disinvestment in these areas. This also increased the number of people living in poverty in these areas. In Northern Kentucky, flood-prone areas ended up being red-lined, which further discouraged investment in them. Even after flood control measures were completed in the 1940s, many of the areas remained on a downward trend. Making urban renewal efforts and funding more attractive to city leaders and residents of more affluent areas. The Covington Central Riverfront was one area targeted for urban renewal in the 1960s because of this trend. At the time, the city was desperate for additional tax revenue to mitigate the de-industrialization it was experiencing, which led to Covington becoming one of the most economically and socially distressed cities in the United States for a time between the late 1960s and mid-1980s.

This map shows the affected area of the 1937 flood and the IRS footprint.

As a result of the mass exodus and the riverfront distress, the site was seen as a logical and cost-effective place to build a new facility that would boost the city’s finances. Older 19th Century and early 20th Century houses and buildings, like those on the site, were seen by society at the time as being largely disposable, archaic relics of a bygone time that no longer had value and would never have value again.

And thus, in the 1960s, it became the perfect site for the new IRS facility, but not only did that area become demolished for the facility, a sizable portion of was also claimed for the introduction of Interstate 71/75. So - a whole lot of change was happening on the site.

A significant factor for the changes were the city’s commercial district being re-oriented towards cars and away from pedestrians and transit on a large scale in the latter half of the 20th Century, with many blocks of buildings that formerly housed people and small neighborhood businesses being demolished in favor of parking lots, fast food restaurants, gas stations, and automobile services. This was especially prevalent along Scott, Washington, 3rd, 4th, and 6th Streets, with this happening both adjacent to the central business district centered around Madison and Pike, and along the riverfront between Johnson and Interstate 71/75, stretching southward to the 5th Street corridor. These areas, once home to a mix of commercial, residential, and industrial land uses, today are predominately car-oriented commercial areas with one-story buildings with small footprints surrounded by much larger expanses of parking lots.

This map shows the flood, the IRS, and the I71/75 foot print.

In Covington, 94 acres is occupied by Interstate 71-75, its ramps, bridge approaches, and buffer space. This land was historically predominately parkland in the flood-prone northern section between Pike and the river, but also included a mix of residential, industrial, and commercial development. Around the freeway and downtown Covington, approximately 171 acres of land is utilized less intensively than it was historically, including vacant land where there were once buildings, over-expanded school campuses that were designed and planned with little consideration for the surrounding urban context, surface parking, fast food restaurants, chain hotels with large parking areas, gas stations, and expanded street footprints. Out of these 171 acres, the Covington Central Riverfront site makes up 22.3 acres, and is the largest single piece of uninterrupted land utilized in such a manner.

An actual photo of the Brent Spence Bridge being constructed.

Things used to be built where people needed them, now they’re built to accommodate people with cars. Which is what makes it such an impactful piece of real estate to redevelop now. The city wants to attempt to return it to the historic fabric of different uses (offices, housing, retail, and green spaces). But the modern zoning code and practicalities of development financing and construction won’t allow the organic and uncurated growth of the olden days that took decades to establish.

This map (and the others before it) have the houses and buildings that no longer exist in the pink color, and the remaining ones in light blue.

The challenge is real and important. And unique – nowhere in the country is such a large metropolitan area available for redevelopment. It’s a huge responsibility, we hope that the City makes sure it’s done right. This is a problem that’s going to be difficult to solve because it’s going to require patience, incremental development vs site development control, and site construction control.

Hopefully, the Covington Central Riverfront inspires similar projects across the region on similarly underdeveloped sites, helping to re-densify the cities and reduce suburban sprawl, and create great new places to live, work, and play.

The RFPs are coming out. We’ll know soon.